Social discourse about parenting is often greatly biased towards the mother-child relationship. This is the case not only in everyday discussions but also in psychological research, where the great majority of studies focus on the maternal relationship, implicitly suggesting that it is the most important attachment relationship in the child’s life (Tannenbaum, 2013). Up until the 1970s, research on paternal relationships mainly focused on the absence of a father figure, rather than examining the father’s role in a child’s upbringing (Spetter, 2018). However, things have changed in the last decades, as psychological researchers became curious about the impact that fathers have on their children’s development and future (Pappas, 2012). With Father’s Day approaching, we feel that it is fitting to give credit to the contributive role of males in the family.

Literature suggests that actively present father figures raise healthier and well-adjusted children. This was confirmed by a 20-year-long research review, which consistently found that boys of fathers who are actively present in their lives exhibit less behavioural problems and are less likely to engage in criminal behaviours, while girls are less likely to suffer from psychological issues, when an engaged father was present in their lives (Blackwell Publishing, 2008; Pappas, 2012). Frequent positive contact from the paternal figure also correlates with improved cognitive skills such as intelligence, reasoning and language development, allowing for higher levels of education and social skills to form solid friendships (Blackwell Publishing, 2008).

Indeed, a good father-daughter bond during teenage years prompts healthier romantic relationships accompanied by greater mental and physical well-being by age 33. One study has also shown how a strong father-daughter relationship is a predictor for girls to grow up into women who adaptively handle day-to-day stressors (Blackwell Publishing, 2008).

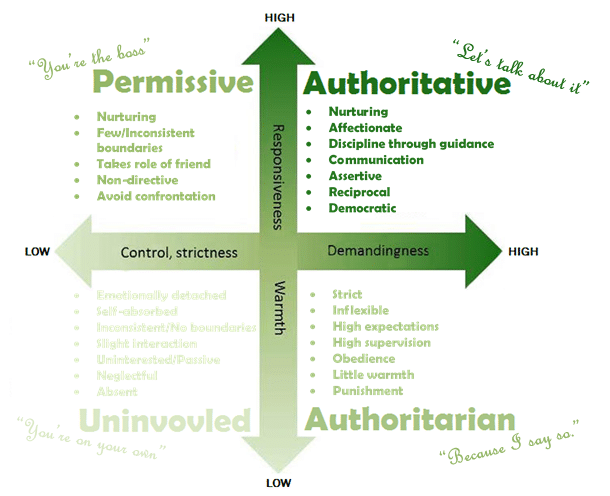

With this being said, one might question what the “right” paternal parenting style is, particularly given the overwhelming amount of information that parents are bombarded with on a daily basis. Diana Baumrind’s typology of four parenting styles is typically used to explain different styles of parenting, consisting of; authoritative, authoritarian, permissive and neglectful. Research shows that authoritative parents foster happier, self-confident and emotionally regulated children (Cherry, 2019). Authoritative parenting is warm, accepting, attentive to feelings and opinions, allows for discussions, cultivates independence yet sets rules, boundaries and consequences. Basically, expectations and demands are high but supported through a warm and caring nature.

More so, research on parenting suggests that positive child development is more closely related to the parenting style rather than gender. Although literature seems to suggest that the absence of a father leads to an array of behavioural and emotional issues, critics have argued that this is linked to the fact that comparative studies of single-parenthood are often based on families who have experienced divorce or separation (Walsh, 2013). It is thus argued that experiencing marital conflict and living in a stressful environment are the root of childhood negative outcomes, rather than the lack of a father figure (Lamb, 2010). To back this up, studies on children raised by single parents whose father had passed away at their young age, showed they developed better than children who had just witnessed a divorce (Biblarz & Gottainer, 2000).

It seems like the absence of a loving parent in general is linked to negative outcomes for a child. Apart from the obvious emotional deprivation, the absence of a co-parent means that parental responsibilities and duties all fall on a single, exhausted parent. Hence, when one looks at research on the effects of an absent-father, such variables must be taken into consideration (Walsh, 2013).

Although research on the topic is not as extensive yet, results show that children raised by lesbian mothers, lesbian couples and gay male parents do not display significant negative outcomes from the lack of a father or mother figure (Stacey & Biblarz, 2001; American Academy of Pediatrics; 2002, Johnson & O’Connor, 2002; Stacey, 2006). The same goes for children who have been raised by their grandparents, when socio-economic factors are not disruptive (Edwards & Andrew, 2006).

Such findings nullify the concept that married, hetero-sexual couples are the gold-standard for childrearing. It rather reinforces the idea that parenting style, i.e., warmth, supportiveness, presence – dictates the development of the child.

Nonetheless, in a society which still puts most of the pressure and responsibility of child-rearing on the female, it is important to allow for opportunities to involve males in every aspect of the child’s life from the very first stages – from attending healthcare appointments, parents’ day, sports events and school pantomimes. Father-friendly policies are a valuable tool on which we are missing out. For instance, issues such as lack-of or limited paternal leave inhibit dads’ involvement in the child’s early years of life (Blackwell Publishing, 2008).

Positively reinforcing males who make their parenting role a priority and encouraging the communication of attention and affection between father and child is beneficial to the child, the family and society at large. Men yearn for, appreciate and enjoy their children’s affection however showing affection to one’s father may be difficult, especially if it is not in the norm of your relationship of family to do so. Still, affection does not require bear hugs and kisses. Active listening and a genuine interest are a good start to show your feelings of acknowledgment and gratitude. Moreover, in this day and age of constant phone communication – the sharing of an article, song or image is a good way to show your dad you thought of him (Spetter, 2018). These small gestures support positive connection and pave the way to more direct forms of expressing one’s feelings.

Wishing a good Father’s Day to everyone!

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2002). Coparent or Second-Parent Adoption by Same-Sex Parents. Pediatrics, 109, 339-334.

- Biblarz, T. J., & Gottainer, G. (2000). Family Structure and Children’s Success: A Comparison of Widowed and Divorced Single Mother Families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(2), 533-548.

- Blackwell Publishing Ltd.. (2008, February 15). Children Who Have An Active Father Figure Have Fewer Psychological And Behavioral Problems.

- Cherry, K. (2019, March 11). Do You Have an Authoritative Parenting Style?

- Edwards, O, W., & Daire, A, P. (2006). School-age children raised by their grandparents: Problems and solutions. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 33 (20), p113-119.

- Hoffman, L. (2019, May 29). Thoughts About Fatherhood and Father’s Day in the #Metoo Era.

- Johnson, S., & O’Connor, E. (2002). The gay baby boom: The psychology of gay parenthood. New York: New York University Press.

- Pappas, S. (2012, June 15). The Science of Fatherhood: Why Dads Matter.

- Spetter, D. (2018, April 04). The Role of Fathers in Childhood Development.

- Stacey, J. (2006). Gay Parenthood and the Decline of Paternity as We Knew It. Sexualities, 9(1), 27-55.

- Stacey, J., & Biblarz, T. J. (2001). (How) Does the Sexual Orientation of Parents Matter? American Sociological Review, 66(2), 159.

- Tannenbaum, M. (2013, June 16). Happy Father’s Day! The Psychology of Papas.

- Walsh, A. (2013). Are Fathers Necessary For Positive Child Development? Student Psychology Journal, 1-14.